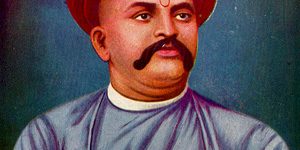

Prin. Vaman Shivaram Apte came from a well-to-do family in Konkan. In the Marathi State of Sawantwadi, in the small village of Asolopal (Banda Peta) his father was known as a noble-minded Pandit of high integrity of character. But his obliging nature brought the family to straitened circumstances at the time of his death, for standing surety for a friend. Vaman was then only eight years old. He was born in 1858 in the same village and had his primary education there.

His mother, a brave lady, saw no future for the family in that native place and came to Kolhapur with her two sons (Vaman and his elder brother) and with great difficulty brought up her children. But she and her first son succumbed to death within three years and Vaman was left orphan. However, his sharpness and brilliancy won him the favour of Shri. M. M. Kunte, the Head Master of the Rajaram High School and a reputed, scholar and hence Vaman’s school-career was completed without much hardship.

He passed the Matriculation examination and secured more than 90% of the total marks, with the unique Sanskrit scholarship, named after Jagannath Shankarshet. Prof. Kielhorn wanted him to study in the Deccan College directly under him. There too Vamanrao showed his brilliance in all examinations and won the Bhau Daii Sanskrit Prize at the B. A. examination (1877) and the Bhagawandas Scholarship at the M. A. examination(1879). With these distinctions Government service of a very high grade would have been very easy for him. But he had kept before his eyes the patriotic ideas, some of which had already been brought into practice by Vishnu Shastri Chiplunkar, the father of the modern Marathi and of national education. Apte decided once for all to devote himself to the cause of national education by joining the founders of the New English School in 1880, in its first year. Of course, the institution (New English School ) made a most precious acquisition in getting the services of V. S. Apte, in the very beginning of its career. His was a most precocious and penetrating intellect and the record of his academic achievements was most distinguished. Sanskrit was his special forte. He was a born teacher and a strict disciplinarian. The founders of the institution recognised his pre-eminent merits and invested him with the office of the Superintendent, while the patriarch Chiplunkar himself worked under him as the Head Master. Apte’s labors bore speedy fruit in as much as the school carried off one of the two Sanskrit scholarships at the Matriculation examination, even in the first year.

On the 9th September 1889, Apte placed the considerate views of the conductors of the New English School on the subject of Education, before the Bombay Provincial Educational Reforms Committee, presided over by William Hunter, the substance of which is as follows: –

Apte protested against the teaching of the Bible in aided Missionary schools and colleges as militating against the principle of religious neutrality, enunciated in the Despatch of 1854. He also expressed the opinion that Missionary institutions did not represent indigenous enterprise, nor were their objects purely educational, and hence a strict adherence to the principles of the Despatch would make them ineligible for grant-in-aid.

A strong plea was put in by him for perfect freedom of management in internal organisation, to be given to educational institutions, provided the requisite degree of efficiency was maintained. He pleaded that secondary schools might be left free to reach the goal of the Matriculation standard, by whatever course they thought best.

A searching criticism of the curriculum in primary and secondary schools was offered by him. Vernacular Serial Reading Books were described by him as being “exactly what they should not be”, being too abstruse and full of matter, far removed, from the experience and observation of boys.

In his opinion, the denationalising tendency of a good deal that was associated with English education must be corrected and one of the ways of doing so should be to encourage indigenous effort in the field of education and leave to it scope for free development according to the ideas, needs and requirements of the community served by it. Religious instruction of the dogmatic and ritualistic land was disapproved, but moral instruction designed to inculcate love of private and public virtue and to arouse and fortify the sense of duty in the students’ minds towards society and the country, was pronounced to be desirable. The most serious defect in the course of the secondary education was the place of exaggerated and unnatural importance that English held in secondary education. As vernaculars were neglected, in secondary schools and altogether proscribed, from the degree courses, the direct contribution of the University to the building up of high class literature in vernaculars was practically nil. Vernaculars ought to be given an honoured place in the scheme of English education at schools and colleges.

The system of assigning grants-in-aid to schools was also severely criticised, by Apte. He pleaded for a mixed system of grants, such as would, introduce an element of continuity and stability while preserving the incentive to exertion which was the redeeming feature of the system of payment by results. Under the mixed system, grants were to be partly given according to the qualifications of teachers employed and partly according to the results of the departmental examination.

Such reforms are still required and Apte’s evidence before the Hunter Commission is very valuable to educationists even to-day.

The project of starting a college of their own was also put before the Commission, on behalf of the promoters of the New English School as an integral part of their scheme of national or public education.

Apte strove hard for the formation and constitution of the Deccan Education Society. When there was some controversy among the life-members of the Society regarding the activities of the members, other than those directly connected with the School, he put up a spirited defense of the extra-school undertakings of the managers. “We thought of employing the time at our command, in instructing ourselves, instructing the people and writing books for the use of our school”. Some promoters of the Society like Lok. Tilak and Agarkar interested themselves like Apte, in public work of a varied character and could do so without detriment to the success of the institution.

When the N. E. School and the Fergusson College were marching from success to success, the man to whom, more than any one else, the credit of planning for and achieving these successes was due, passed away on the 9th August 1892.

In spite of the short span of his life, i.e. 34 years, Apte’s scholarly output was remarkable. His Guide to Sanskrit Composition (1881) and his Sanskrit Dictionaries for use in schools and

PRINCIPAL V. S. APTE

Prin. Vaman Shivaram Apte came from a well-to-do family in Konkan. In the Marathi State of Sawantwadi, in the small village of Asolopal (Banda Peta) his father was known as a noble-minded Pandit of high integrity of character. But his obliging nature brought the family to straitened circumstances at the time of his death, for standing surety for a friend. Vaman was then only eight years old. He was born in 1858 in the same village and had his primary education there.

His mother, a brave lady, saw no future for the family in that native place and came to Kolhapur with her two sons (Vaman and his elder brother) and with great difficulty brought up her children. But she and her first son succumbed to death within three years and Vaman was left orphan. However, his sharpness and brilliancy won him the favour of Shri. M. M. Kunte, the Head Master of the Rajaram High School and a reputed, scholar and hence Vaman’s school-career was completed without much hardship.

He passed the Matriculation examination and secured more than 90% of the total marks, with the unique Sanskrit scholarship, named after Jagannath Shankarshet. Prof. Kielhorn wanted him to study in the Deccan College directly under him. There too Vamanrao showed his brilliance in all examinations and won the Bhau Daii Sanskrit Prize at the B. A. examination (1877) and the Bhagawandas Scholarship at the M. A. examination(1879). With these distinctions Government service of a very high grade would have been very easy for him. But he had kept before his eyes the patriotic ideas, some of which had already been brought into practice by Vishnu Shastri Chiplunkar, the father of the modern Marathi and of national education. Apte decided once for all to devote himself to the cause of national education by joining the founders of the New English School in 1880, in its first year. Of course, the institution (New English School ) made a most precious acquisition in getting the services of V. S. Apte, in the very beginning of its career. His was a most precocious and penetrating intellect and the record of his academic achievements was most distinguished. Sanskrit was his special forte. He was a born teacher and a strict disciplinarian. The founders of the institution recognised his pre-eminent merits and invested him with the office of the Superintendent, while the patriarch Chiplunkar himself worked under him as the Head Master. Apte’s labors bore speedy fruit in as much as the school carried off one of the two Sanskrit scholarships at the Matriculation examination, even in the first year.

On the 9th September 1889, Apte placed the considerate views of the conductors of the New English School on the subject of Education, before the Bombay Provincial Educational Reforms Committee, presided over by William Hunter, the substance of which is as follows: –

Apte protested against the teaching of the Bible in aided Missionary schools and colleges as militating against the principle of religious neutrality, enunciated in the Despatch of 1854. He also expressed the opinion that Missionary institutions did not represent indigenous enterprise, nor were their objects purely educational, and hence a strict adherence to the principles of the Despatch would make them ineligible for grant-in-aid.

A strong plea was put in by him for perfect freedom of management in internal organisation, to be given to educational institutions, provided the requisite degree of efficiency was maintained. He pleaded that secondary schools might be left free to reach the goal of the Matriculation standard, by whatever course they thought best.

A searching criticism of the curriculum in primary and secondary schools was offered by him. Vernacular Serial Reading Books were described by him as being “exactly what they should not be”, being too abstruse and full of matter, far removed, from the experience and observation of boys.

In his opinion, the denationalising tendency of a good deal that was associated with English education must be corrected and one of the ways of doing so should be to encourage indigenous effort in the field of education and leave to it scope for free development according to the ideas, needs and requirements of the community served by it. Religious instruction of the dogmatic and ritualistic land was disapproved, but moral instruction designed to inculcate love of private and public virtue and to arouse and fortify the sense of duty in the students’ minds towards society and the country, was pronounced to be desirable. The most serious defect in the course of the secondary education was the place of exaggerated and unnatural importance that English held in secondary education. As vernaculars were neglected, in secondary schools and altogether proscribed, from the degree courses, the direct contribution of the University to the building up of high class literature in vernaculars was practically nil. Vernaculars ought to be given an honoured place in the scheme of English education at schools and colleges.

The system of assigning grants-in-aid to schools was also severely criticised, by Apte. He pleaded for a mixed system of grants, such as would, introduce an element of continuity and stability while preserving the incentive to exertion which was the redeeming feature of the system of payment by results. Under the mixed system, grants were to be partly given according to the qualifications of teachers employed and partly according to the results of the departmental examination.

Such reforms are still required and Apte’s evidence before the Hunter Commission is very valuable to educationists even to-day.

The project of starting a college of their own was also put before the Commission, on behalf of the promoters of the New English School as an integral part of their scheme of national or public education.

Apte strove hard for the formation and constitution of the Deccan Education Society. When there was some controversy among the life-members of the Society regarding the activities of the members, other than those directly connected with the School, he put up a spirited defense of the extra-school undertakings of the managers. “We thought of employing the time at our command, in instructing ourselves, instructing the people and writing books for the use of our school”. Some promoters of the Society like Lok. Tilak and Agarkar interested themselves like Apte, in public work of a varied character and could do so without detriment to the success of the institution.

When the N. E. School and the Fergusson College were marching from success to success, the man to whom, more than any one else, the credit of planning for and achieving these successes was due, passed away on the 9th August 1892.

In spite of the short span of his life, i.e. 34 years, Apte’s scholarly output was remarkable. His Guide to Sanskrit Composition (1881) and his Sanskrit Dictionaries for use in schools and colleges hold the foremost place among books of their kind, even after the lapse of close upon 75 years and claim the respect of every student of Sanskrit, by their monumental wealth of learning. His death was a great loss to the advance of Sanskrit studies in India. He was a combination of the scholar and the administrator. He was a disciplinarian, who knew how to temper discipline with kindness. People used to say of him with great admiration that he could turn a dunce into a Jagannath Shankarshet scholar if he meant it. For, in his regime the N. R. School won this scholarship nine times between the years 1880 and 1892. Reputed Sanskrit scholars like Prin. V. K. Rajawade, Prof. L. 6. Lele, Prof. S. N. Paranjape and some others were his students. He enjoyed the full confidence of his colleagues and was made the permanent principal of the Fergusson College. During the period of his principalship, he was as well the Superintendent of the New English School and Secretary of the Deccan Education Society for some time.

His works: –

- The Practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary (1890).

- The Students’ English-Sanskrit Dictionary (1884).

- The Students’ Sanskrit-English Dictionary.

- The Students’ Guide to Sanskrit Composition (1881).

- The Students’ Hand-Book of Progressive Exercises, Part I and, II.

- Kusuma-mala (1891).

The ‘Guide’ had become very popular and Apte himself revised the third edition of the book in 1890. Since then many more editions have been out.

Of all the books prepared by him the Practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary gave him a permanent name. This unique work, was brought out by him single-banded and its worth cannot be exaggerated. The author has given the plan and scope of this work in the Preface (which is embodied in the present revised edition) which speaks for itself. In its conclusion, he says, “I may be permitted to express the hope that the Practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary, which has attempted to give in 1900 closely printed pages of this size, matter at least equal in point of quantity to that given by Prof. Monier Williams in his Dictionary, but in, point of quality more reliable, varied and practically useful, in my humble opinion, will serve the purpose I have had in view in compiling it; namely, to render to the student of Sanskrit nearly the same service that Webster’s or Ogilvie’s Dictionary does to the student of English.” This purpose, no doubt has been served, through all these years and quite efficiently.

Very little is known about his family life. His wife was the daughter of the reputed patriot and public worker in Maharashtra- the ‘Sarvajanik Kaka’ (G. V. Joshi ). The marriage took place in 1876. He had only one child, a daughter Godavari by name who was later on married to Shri. Parashuram Damodar Joag of Tasgaon. Now her children (grandsons of V. S. Apte) are serving in high posts and try to keep up the memory of their illustrious grand-father.